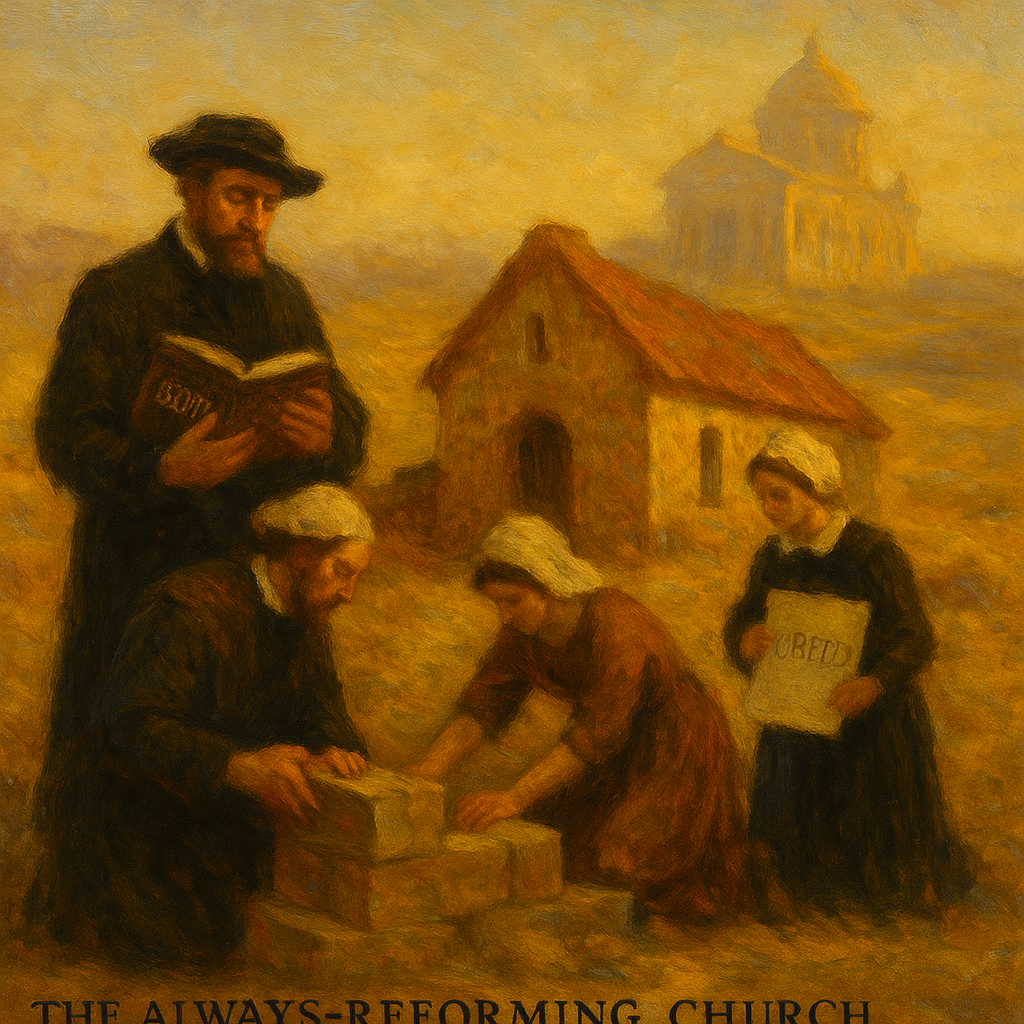

(Image created with AI assistance by ChatGPT (OpenAI)).

Cameron Bertuzzi, a Roman Catholic apologist, recently posted a video on his Capturing Christianity channel arguing against sola scriptura. One of his primary arguments was that a system including not just Scripture but also inspired tradition and an authoritative magisterium is more “parsimonious”—more elegant and complete. He claimed it was “perfect in principle,” while sola scriptura was “arbitrary” and inconsistent.

As a former Latter-day Saint, Bertuzzi’s argument was very familiar. Indeed, LDS leaders frequently appeal to the beauty or elegance of the LDS system of continuing revelation to Prophets and Apostles.

And there is some appeal to both of their arguments. It’s true: both Catholicism and Mormonism offer models of church authority that, in theory, seem more streamlined than Protestantism. A central decision-making body, visible unity, and living authority figures are all, on the surface, attractive.

But there are three major problems with this appeal:

(1) the appeal to parsimony cuts both ways,

(2) parsimony breaks under real-world theological and historical weight, and

(3) the pursuit of parsimony can entrench error rather than correct it.

1. Parsimony Cuts Both Ways

Mormonism and Catholicism are actually perfect foils to each other in this regard.

Catholics can claim it’s more elegant to have a unified historic church with an infallible Magisterium. But they also assert that the age of public revelation has ended. That leaves them with a visible institution—but no living apostles receiving new revelation. From a Mormon perspective, that’s an arbitrary stopping point, and not especially elegant.

Meanwhile, Latter-day Saints can claim that continuing revelation through living prophets mirrors the early Church and is more direct and dynamic. For instance, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland argued, “the presence of such authorized, prophetic voices and ongoing canonized revelations have been at the heart of the Christian message whenever the authorized ministry of Christ has been on the earth.” But to get there, they must posit a complete apostasy of Christ’s Church, a centuries-long loss of priesthood authority, and a restoration through Joseph Smith involving new scripture and radically redefined doctrines—including an exalted, once-mortal God. That’s hardly a parsimonious model.

This highlights the weakness of relying on theoretical and subjective appeals to elegance or simplicity.

2. Parsimony Breaks Under the Weight of Reality

Scripture itself paints a messier picture of Church leadership. In Acts, we glimpse moments of miraculous unity—but they are fleeting. The early church wrestled with ethnic tension (Acts 6), internal deceit (Acts 5), and disagreements over mission strategy (Acts 15:36–41). Galatians 2 reveals that even Peter, post-Pentecost, fell into hypocrisy and was publicly opposed by Paul. This is not evidence of institutional failure; it’s a picture of how God works through imperfect vessels, with Scripture and the gospel as the ultimate standard. That’s the real world: not tidy elegance, but fallible humans in need of ongoing reform.

Sure, it would theoretically be wonderful to be led by an infallible magisterium or by a prophet who regularly speaks with Jesus in the temple. But if these things are not true, then no amount of appeal to elegance or parsimony can make it so. Parsimony isn’t proof. Beauty and coherence may be attractive, but they don’t establish what is true.

And the parsimony of both Catholicism and Mormonism breaks under the weight of reality. Both systems collapse under the weight of the extra baggage they require. When examined closely, their supposed elegance gives way to theological complexity, historical inconsistency, and institutional faults.

Catholic history includes morally compromised popes like Pope Honorius or the Avignon Papacy, ongoing doctrinal disputes, and significant accretions like icon veneration and the Marian dogmas. Mormonism has seen major prophetic contradictions—from Brigham Young’s Adam-God doctrine to evolving teachings about Blacks and the priesthood and temple ordinances. And both systems have also been prone to splintering and factions.

Meanwhile, both systems deliver far less than they promise. The Catholic Magisterium does not provide clarity on disputed biblical doctrines and texts. And modern Mormon Prophets and Apostles run away from the bold and decisive truth claims of early generations of LDS leaders, leaving ambiguity and a lack of doctrinal clarity.

3. The Pursuit of Parsimony Can Be a Trap

If, in pursuit of parsimony, we hold up fallible teachers as infallible, then we are setting ourselves up for moral and spiritual disaster. The truth is that real-world authority structures inevitably face doctrinal failures. Systems that can’t correct course (because they claim infallibility or prophetic revelation) become more dangerous, not more trustworthy.

As I wrote about previously, following a false prophet or magisterium can be incredibly destructive. When false teaching becomes ossified, correction becomes rebellion. We can fall into spending more time defending our leaders than pursuing the truth. All the while, we slip further and further away from the Gospel.

As Gavin Ortlund expressed in his Book What it Means to be Protestant: ““while erroneous private judgment [of the Bible] is a real danger, another danger is far worse: erroneous ecclesiastical judgments. It is one thing to be able to err; it is another to be yoked to error”

The Protestant Antidote: Semper Reformanda

So what hope is there? Are we doomed to apostasy and failure?

The genius of the Reformation was a recognition that, because human nature constantly drifts into error, the church must always be testing itself against Scripture. This is the spirit of semper reformanda—“always reforming.” This insight is rooted in humility and a recognition of human fallibility.

As Gavin Ortlund puts it:

“Protestantism has a built-in capacity for course correction, for fixing errors, for refining practice. To put it colloquially, when you get stuck, you can get unstuck. This opens up pathways for catholicity that are closed for those churches that hold their own pronouncements as infallible”

At its best, this impulse allows the Church to avoid the rigidity of infallible structures and to sidestep the danger of ossified falsehood. Yes, this leads to denominational diversity—but that diversity allows errors to be challenged, rather than locked in. Better to have a system that is always testing itself by the Word of God than one that is paralyzed by its own supposed infallibility.

Semper reformanda is parsimonious in its own beautiful way. It is based on the belief that God has already spoken clearly in Scripture, so no new magisterium or prophet is needed. In other words, it is rooted in the clarity and timelessness of God’s revealed truth. The sufficiency of God’s Word provides the authority we need—without the burden of sustaining fragile claims to infallibility.

As Pastor Kevin DeYoung explained, “Semper reformanda is not about constant fluctuations, but about about firm foundations. It is about radical adherence to the Holy Scriptures, no matter the cost to ourselves, our traditions, or our own fallible sense of cultural relevance.”

Or as Isaiah declared, “The grass withers, the flower fades, but the word of our God will stand forever,” (Isaiah 40:8)

The Protestant Reformers didn’t abandon authority—they re-centered it. Not in men, but in the Word. And that is ultimately likely the most elegant solution of all.