In the last few days my social media feed has been filled with a back and forth between orthodox Christians, generally but not always Evangelical Protestants, and Latter-day Saints. The orthodox Christians argue that Latter-day Saints depart from Christian orthodoxy in fundamental ways and therefore are not Christian. Meanwhile the Latter-day Saints respond by pointing out that the name Jesus Christ is in the name of their church and that as a community they exemplify Christian virtues. These conversations tend to generate a lot of acrimony and hurt feelings and are unfortunately very unhelpful.

The problem is that Latter-day Saints and orthodox Christians are using the term “Christian” in different ways and this leads the two groups to talk past each other.

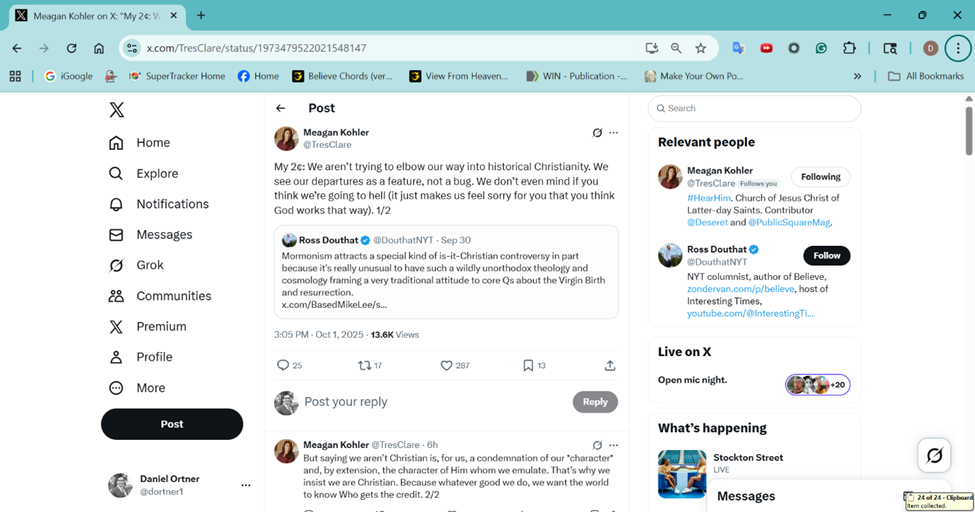

A Latter-day Saint friend of mine, Meagan Kohler, pointed this out really succinctly on X:

Meagan: My 2¢: We aren’t trying to elbow our way into historical Christianity. We see our departures as a feature, not a bug. We don’t even mind if you think we’re going to hell (it just makes us feel sorry for you that you think God works that way). ½

Meagan: But saying we aren’t Christian is, for us, a condemnation of our character and, by extension, the character of Him whom we emulate. That’s why we insist we are Christian. Because whatever good we do, we want the world to know Who gets the credit. 2/2

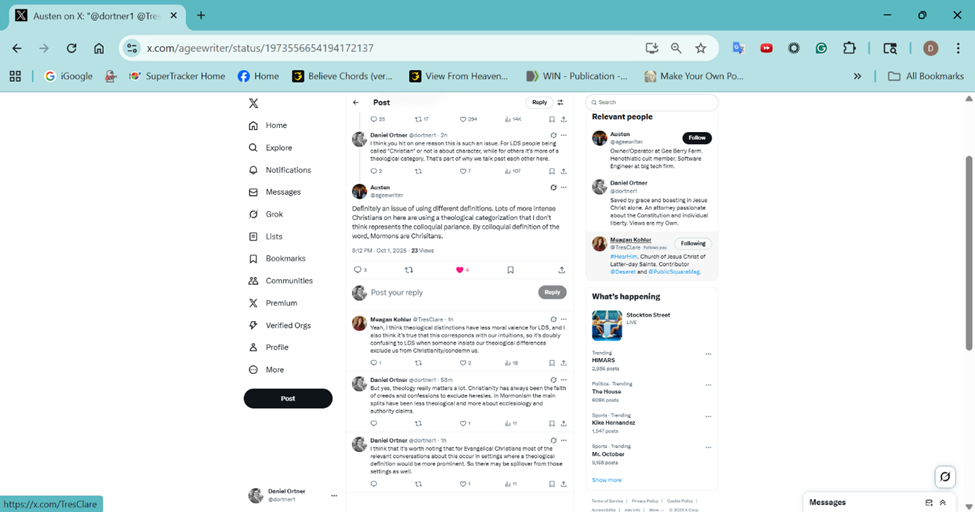

Here’s the rest of the conversation:

Me: I think you hit on one reason this is such an issue. For LDS people being called “Christian” or not is about character, while for others it’s more of a theological category. That’s part of why we talk past each other here.

Meagan: Yeah, I think theological distinctions have less moral valence for LDS, and I also think it’s true that this corresponds with our intuitions, so it’s doubly confusing to LDS when someone insists our theological differences exclude us from Christianity/condemn us.

Me: I think that it’s worth noting that for Evangelical Christians most of the relevant conversations about this occur in settings where a theological definition would be more prominent. So there may be spillover from those settings as well.

Me: But yes, theology really matters a lot. Christianity has always been the faith of creeds and confessions to exclude heresies. In Mormonism the main splits have been less theological and more about ecclesiology and authority claims.

For Latter-day Saints, being called “not Christian” feels like an attack on their character. It suggests a lack of morality and uprightness. Since being a Christian is understood less in terms of doctrinal belief and more in terms of living out the teachings of Jesus, denying them the title feels like a personal condemnation.

That sting is compounded by LDS history: early Latter-day Saints were often treated as outsiders and even enemies of society—driven from Missouri under threat of extermination, and later forced from Nauvoo. Against that backdrop, being told they are “not Christian” can sound less like a theological clarification and more like a continuation of historic exclusion.

On the other hand, for orthodox Christians, and especially for Evangelicals, being Christian involves being united on core theological doctrines. This has been the orthodox Christian heritage from the start. From the New Testament epistles warning against false teachings, to the creeds and confessions formulated in response to heresies, right doctrine has always been central. The Council of Nicaea, for example, didn’t condemn Arianism because Arians lacked devotion or morality, but because they denied the divinity of Christ—a core truth of the gospel. That is the tradition orthodox Christians see themselves standing in when they draw doctrinal lines today.

This is why orthodox Christians insist that saying Latter-day Saints are not Christian is not a reflection on character but on theology. I know many Latter-day Saint friends who live more exemplary lives and have better “Christian” character than I do. But that is not the question at issue.

Still, for a Latter-day Saint, being labelled non-Christian hearkens back to rejection and persecution. That helps explain why the awful shooting this week, coupled with some orthodox Christian responses online, felt so traumatizing and triggering for many.

This conversation with Meagan was eye-opening for me because it crystalized what I had been thinking all day. I’ve been brainstorming whether there is a way to differentiate between orthodox Christians and Latter-day Saints that still acknowledges the LDS connection to Christianity without compromising on the the distinctiveness of orthodox Christianity. A few options that stood out are “Christian adjacent,” “Christian affiliated,” or “heterodox Christians.” I’ve already been using “orthodox Christian” in this article to test it out. But I am not sure yet whether “heterodox” or “non-orthodox” hit the right notes. Still I think heterodox Christians might be a useful title for groups like Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, or Unitarians—groups that draw deeply from Christian language and story but whose theology departs from the boundaries of orthodoxy. What do you think?

Regardless of the titles we use, another thing orthodox Christians can do is pick their battles more carefully. For instance this week when President Trump referred to the victims of the Michigan shooting as Christians, that was not a theological statement of orthodoxy but a broad recognition that Latter-day Saints are a Christian-adjacent community, broadly affiliated with Christianity in the cultural sense. We do not need to fight every battle or defend every bit of turf.

When the conversation shifts to matters of theology and salvation, then it may be necessary to take a firmer stance. But as we do so, we should be clear that we are speaking about doctrine, not character, and we should emphasize that distinction. Latter-day Saints, for their part, can do more to recognize how deeply theology matters to orthodox Christians, and that boundary-setting is not necessarily about moral condemnation but about fidelity to the gospel as Christians have understood it since the beginning.

Perhaps the better question is not, “Are Latter-day Saints Christian?” but, “In what sense are they Christian?” If both sides can recognize that they are using the same word with very different meanings, then instead of endless disputes over labels, we can have clearer and more fruitful conversations about the very real and important theological differences that remain.